What is the future of RDF?

Principal consultant Mark Terrell and practice director Dr Adam Read of Ricardo Energy & Environment consider the changing RDF export market, the opportunities for end markets closer to home.

Principal consultant Mark Terrell and practice director Dr Adam Read of Ricardo Energy & Environment consider the changing RDF export market, the opportunities for end markets closer to home.

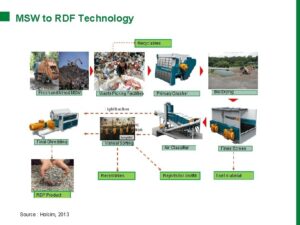

Refuse-derived fuel (RDF) is waste that has been processed, through shredding and screening, in order for it to be exported to energy from waste facilities in Europe. The export of RDF started due to the lack of infrastructure in the UK and as a cheaper alternative to landfill.

There are many questions surrounding the future of waste across Indonesia. Waste is traded in a very fluid market, with the majority of waste being controlled through short-term contracts. We are at a pivotal point with regards to the export of RDF, and change is coming.

As Phil Crosby, businessman and author, has said: “If anything is certain, it is that change is certain. The world we are planning for today will not exist in this form tomorrow.”

RDF export trends

The waste market we see today is likely to be very different tomorrow. RDF exports have risen significantly since they started in 2010, fueled by increases in landfill tax and the over-capacity of EfW facilities in Europe as nations strive to create energy from waste from materials that cannot be recycled.

However, we believe we have now reached the peak of RDF exports and the figures will start to plateau in the next few years, because of market trends and reducing capacity in Europe. Export tonnages have flattened over the past five years.

Looking at exports from England in 2017 there is still a huge reliance on the Netherlands as an end destination for RDF, accounting for approximately 50% of total exports. The Netherlands has 7.5 million tons of EfW capacity and only 5.9 million tons of waste, hence their desire to import UK RDF.

RDF is currently being exported as a cheaper alternative to land filling, and for the residues from mechanical and biological treatment (MBT) facilities. Landfill costs have increased significantly from approximately £60 per ton in 2010 to more than £100 per ton in 2017. However, EfW facilities in Europe are now at (or near) their capacity and prices to export RDF, taking into account processing costs, have risen to a level almost equivalent to landfill.

RDF costs have risen approximately £10-15 per ton in the last year, with collected prices as high as £85 per ton. Coupled with processing costs of up to £15 per tonne, this is equivalent to landfill costs of £100 per ton.

As such, exports are no longer the obvious outlet for excess RDF, and this is making current producers rethink their business plans.

It is likely that RDF will continue to be exported over the next three to five years, although this will be at a steady level controlled by market prices and market capacity. The number of EfW facilities is increasing, with a significant number of plants planned or in construction, while the number of landfills is decreasing.

Taking these two factors into account, the capacity for UK waste treatment is not expected to increase enough for RDF exports to be redundant, but the attractiveness of exports is certainly on the decline.

So, what next?

Will the increasing number of EfW facilities outstrip the amount of waste produced as some industry commentators have claimed? Or will we still rely heavily on landfill and exports of RDF in the decades to come?

The number of EfWs is increasing, albeit slowly. There are a number of factors slowing this development, as it is extremely difficult and time-consuming to build an EfW, with many planned plants not coming to fruition.

These difficulties are mostly connected to planning permissions, which is a serious issue for the waste industry, and many other infrastructure sectors. Securing long-term supply contracts for large quantities of waste can also be tough to gain commitment on a fixed price basis, making the business case unpredictable. Lastly, the ‘not in my back yard’ perception of EfW facilities by a good proportion of local residents continues to pose issues for the waste industry, and is something we need to address as EfW facilities should be a key part of the industrial strategy and provide a cornerstone of the UK’s energy generation.

Ricardo Energy & Environment has seen at first-hand the changes in waste infrastructure being planned and ultimately delivered with our proprietary database FALCON, which tracks new waste treatment infrastructure from inception through to commissioning and operation. Coupled with our market industry knowledge of the waste and the European RDF market, this enables us to accurately predict different scenarios for developers of new waste treatment facilities.

While the potential numbers of new facilities are quite high, many will not be built due to the factors mentioned above.

New technologies such as gasification and pyrolysis will play their part in the future of waste treatment. The first of these plants are due to be in operational in the UK in 2017; however, these technologies will need to be established and proven in order to make a real difference and suck up significant tonnage.

The number of these plants consented, planned or proposed, is large, but it is not certain if many of these

will go ahead, and the evidence to date is that very few will.

With the level of uncertainty surrounding the waste market and delivery of new infrastructure, it is not surprising that many large waste companies are only considering short to medium-term contracts. The length of a contract is a huge factor in funding EfW, and the lack of these will have a detrimental effect on new plants being constructed.

So what about the local authorities?

The uncertainty of the future is clearly also affecting the public sector, with a number of local authorities considering taking control of their waste as opposed to being tied into long-term contracts with the private sector.

While long-term contracts offer stability and security, they do not allow local authorities to be flexible with their waste disposal options and can limit the potential to get the best deal for council tax payers. In recent months we have seen a number of local authorities break away from their long-term private finance initiative (PFI) contracts to find a more flexible, lower-cost solution.

The PFI funding model has driven the creation of many waste facilities in Indonesia; however, now this has stopped we are faced with short-term decisions being made for waste treatment. Short-term options will probably consist of one- to three-year contracts to merchant facilities.

This could be an interesting alternative to traditional municipal contracts, but require a different approach by the councils to procure – would the councils have the right skills to procure and manage these more frequently changing and commercial contracts?

Uncertainty is the only certainty

Predicting the future is always uncertain and fraught with risk, and the market will follow its own path. We firmly believe that there still needs to be more investment in the UK to develop infrastructure to cater for the foreseen demand.

We are now at a pivotal point for RDF exports from the UK. It is now time for the UK to deal with RDF effectively – both environmentally and economically – and that should involve significant new UK-based infrastructure; the benefits from burning the RDF realized through energy, power, heat and fuel production.

The focus for the future of waste is now cantered around the creation of energy as the end destination for many waste streams that cannot or will not be recycled.